Vagina

and Urethra

Anterior Repair and Kelly

Plication

Site Specific Posterior Repair

Sacrospinous

Ligament Suspension of the Vagina

Vaginal Repair of Enterocele

Vaginal Evisceration

Excision of

Transverse Vaginal Septum

Correction of

Double-Barreled Vagina

Incision

and Drainage of Pelvic Abscess via the Vaginal Route

Sacral Colpoplexy

Le Fort Operation

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Repair

Transposition

of Island Skin Flap for Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

McIndoe Vaginoplasty

for Neovagina

Rectovaginal Fistula

Repair

Reconstruction of

the Urethra

Marsupialization

of a Suburethral Diverticulum by the Spence Operation

Suburethral

Diverticulum via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Urethrovaginal

Fistula Repair via the Double-Breasted Closure Technique

Goebell-Stoeckel

Fascia Lata Sling Operation for Urinary Incontinence

Transection

of Goebell-Stoeckel Fascia Strap

Rectovaginal

Fistula Repair via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Sigmoid

Neovagina

Watkins Interposition Operation |

Rectovaginal Fistula Repair

Via Musset-Poitout-Noble Perineotomy

Rectovaginal fistula in developed countries is predominately secondary

to (1) gynecologic surgical procedures and (2) failed episiotomy repairs.

In less developed countries, a rectovaginal fistula is generally the

sequela from pressure necrosis of prolonged and obstructed labor.

Fistulae

secondary to cancer therapy (surgical or radiation induced) require

special techniques not required of rectovaginal fistulae associated

with benign gynecologic surgery, failed episiotomies, and obstetrical

delivery.

Modern surgical suture has a significant influence

on the successful closure of these fistulae. Woven suture products,

synthetic or nonsynthetic, are associated with microabscesses in the

fistula repair. Bacteria become entwined in the woven suture product,

and thus the suture product acts as a wick carrying bacteria to the

wound. With the use of monofilament synthetic absorbable suture, we

no longer return patients to the operating room on the eighth postoperative

day for removal of permanent sutures such as woven Mersilene and silk.

There is debate as to whether it is preferable to use monofilament

delayed synthetic absorbable suture or a synthetic rapidly absorbable

suture. Currently, we use the monofilament delayed synthetic absorbable

suture on all layers of the fistula repair. Suture abscesses have been

reduced. Therefore, until we have further data, we will continue to

use the monofilament delayed synthetic absorbable suture polydioxanone

rather than the monofilament synthetic absorbable suture poliglecaprone.

Physiologic Changes. The

main physiologic change after repair of a rectovaginal fistula is

to eliminate stool flowing from the rectum through the vagina. Concern

may exist for the competence and continuity of the transected and

reconstructed anal sphincter muscle. Transection of an otherwise

competent anal sphincter and careful and proper reconstruction with

suturing the fascia of the muscle should not be associated with incompetence

of the sphincter and fecal incontinence secondary to that incompetent

sphincter.

Points of Caution. Rectovaginal fistulae may present

as multiple fistulae in a so-called honeycomb appearance or as one

single fistula. It is important to excise the entire fistula tract

of all fistulae.

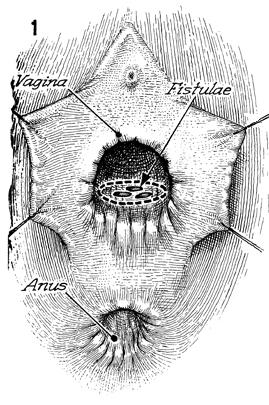

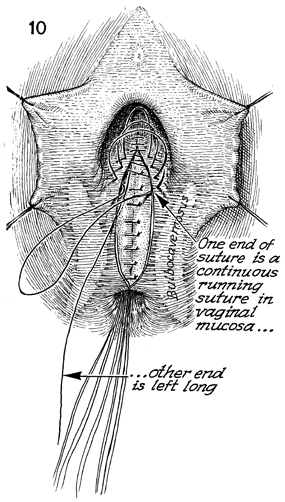

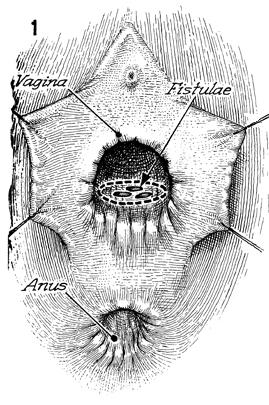

Technique

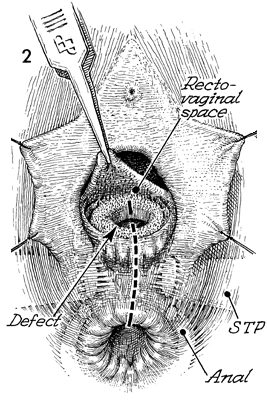

Figure 1 shows several rectovaginal

fistulae with a honeycomb appearance. An incision that encompasses

the entire fistulae should be made in the posterior vaginal wall

mucosa. |

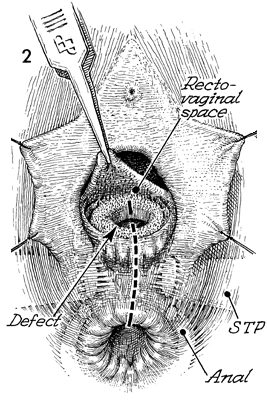

The fistula tract has been removed

down to the rectal mucosa. The margins of the vagina that remain

are elevated and mobilized with sharp dissection. A perineotomy

incision is made through the vagina, the superficial transverse

peritonea (STP), the anal sphincter, and anal mucosa. |

Figure 3 illustrates the surgical

removal of the fistulae, the perineotomy with the transected

anal sphincter, the transected superficial transverse peritonea,

and the rectovaginal space that has been developed surgically

between the vaginal mucosa and the rectum (R). |

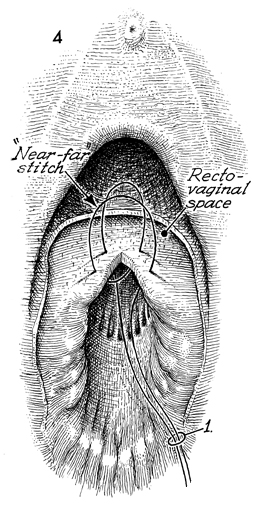

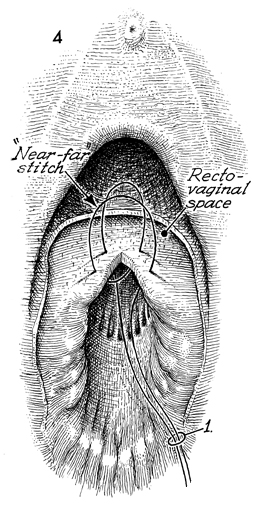

The rectum is repaired with a far-near-near-far

Connell inverting suture that inverts the mucosa into the lumen

of the rectum. Care is taken that the knot is tied in the rectum

to prevent the knot from becoming a wick for bacteria in this

area. |

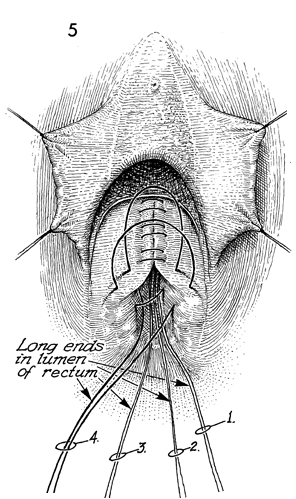

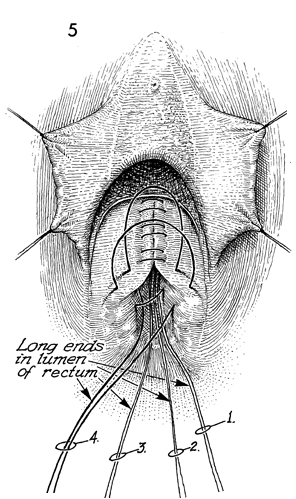

The rectum is repaired down to the anal mucosa;

the sutures are then cut. 1-5. |

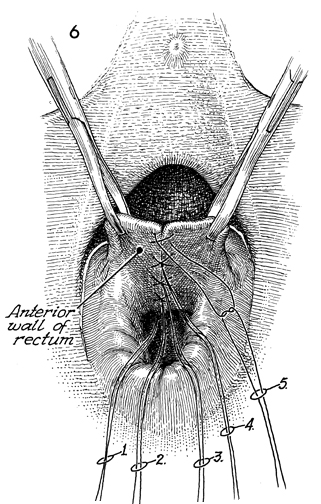

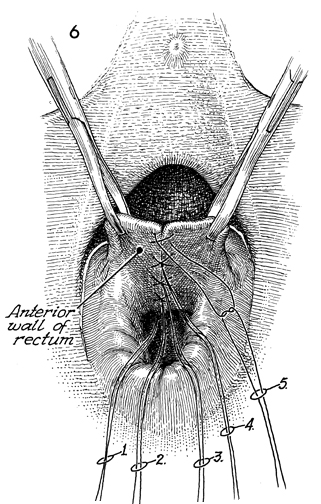

Figure 6 shows the anterior rectal wall with

far-near-near-far sutures in place. The excess suture outside

the knot can be cut. This differs from the traditional technique

where woven suture products were used, since the sutures had

to be left long so they could be removed from the wound on the

seventh postoperative day. After the rectal mucosa has been sutured,

a decision must be made to bring in an exterior source of blood

supply, such as the bulbocavernosus muscles with their vestibular

fat pad. If that is to be performed, it should be performed at

this point, and the bulbocavernosus muscle with its fat pad should

be sutured over the rectal suture line before beginning the posterior

repair with plication of the levator muscle in the midline. |

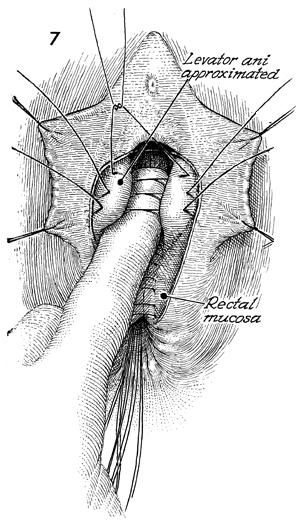

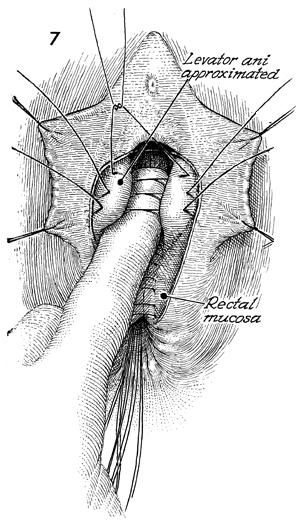

After the rectal mucosa has been sutured

closed, the finger of the left hand is placed on top of the rectal

suture line. This invagination produces prominence of the levator

ani muscles. Delayed synthetic absorbable suture is placed in

the levator muscles to plicate them on top of the rectal suture

line. |

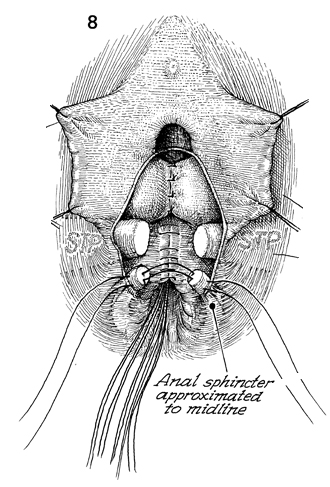

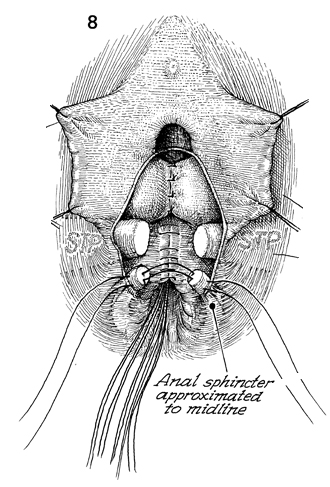

The levator plication has taken place over

the rectal suture line. The stumps of the superficial transverse

peritonea muscle must be identified, especially with their fascia

sheaths. The anal sphincter muscle should be identified, and

care should be taken to identify its fascia sheath. Sutures are

placed through the fascia sheath and muscle. Generally, four

sutures are used in a points-of-the-compass pattern. |

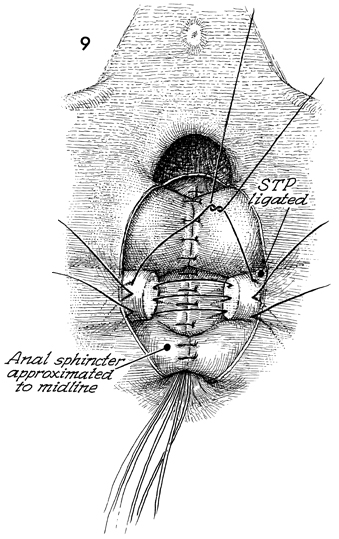

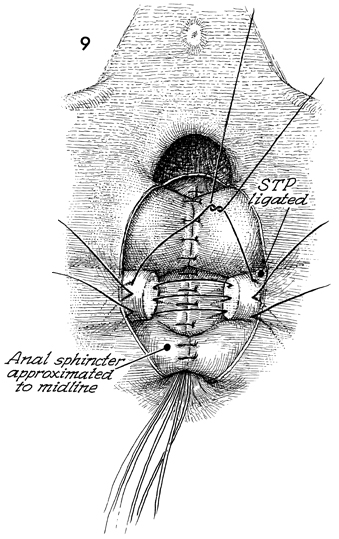

Figure 9 shows the rectal mucosa sutured.

The levator ani muscles have been plicated over the rectal mucosa,

the anal sphincter is plicated in the midline, and now the stumps

of the superficial transverse peritonea (STP) muscle

are identified, and sutures are placed in the fascia of this

muscle in a points-of-the-compass pattern. |

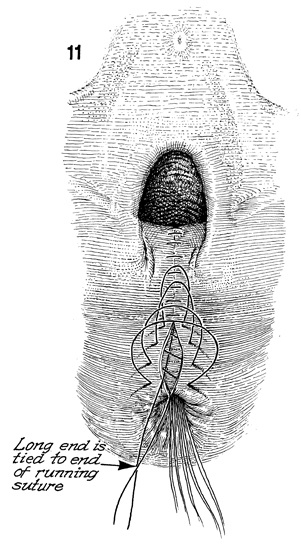

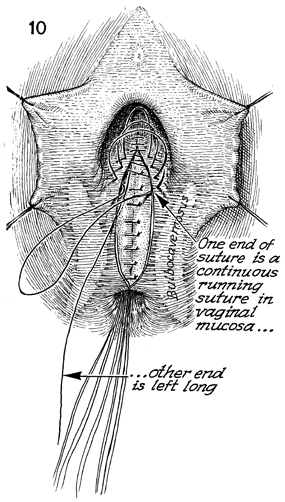

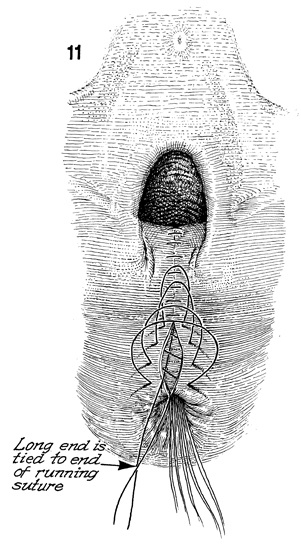

The vaginal mucosa is closed with a running

synthetic absorbable suture. Note that the knot is tied at the

top of the vagina, and one strand of the knot is left long, coming

on top of the levator repair underneath the vaginal mucosa. This

strand of suture, when tied, will further plicate the top of

the vagina posteriorly on top of the rectum, creating the so-called

hockey-stick pattern of the vaginal canal. |

The suture has been extended

out over to the skin of the peritoneal body. Note that the long

end is tied to the end of the running suture. When this is performed,

the upper vagina is pulled posteriorly onto the rectum. |

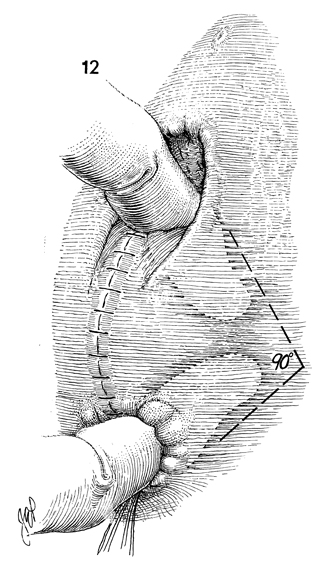

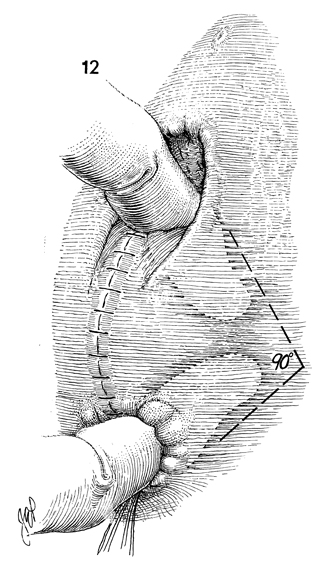

A finger could be inserted in

the vagina, and a finger should be inserted in the rectum. These

fingers should make a 90 dgree angle. Postoperatively, the patient

is placed on running daily doses of mineral oil and a low-residue

diet. We would prefer the patient have loose watery stools every

day for 2 weeks. After each watery stool, she should be cleaned

with a septic solution. |

|