Fallopian Tubes

and Ovaries

Laparoscopy

Technique

Diagnostic

Uses

of Laparoscopy

Demonstration

of Tubal Patency

via Laparoscopy

Laparoscopic

Resection

of Unruptured

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ovarian

Biopsy

via Laparoscopy

Electrocoagulation

of

Endometriosis via

Laparoscopy

Lysis

or Adhesions

via Laparoscopy

Control

of Hemorrhage

During Laparoscopy

Fallopian

Tube

Sterilization

Sterilization

by

Electrocoagulation and

Division via Laparoscopy

Silastic

Band Sterilization

via Laparoscopy

Hulka

Clip Sterilization

via Laparoscopy

Sterilization

by the

Pomeroy Operation

Sterilization

by the

Modified Irving Technique

Sterilization by the

Minilaparotomy Technique

Sterilization - Ucheda Technique

Salpingectomy

Salpingo-oophorectomy

Fimbrioplasy

Tuboplasty

-

Microresection

and Anastomosis

of the Fallopian Tube

Wedge

Resection

of the Ovary

Torsion

of the Ovary

Ovarian

Cystectomy |

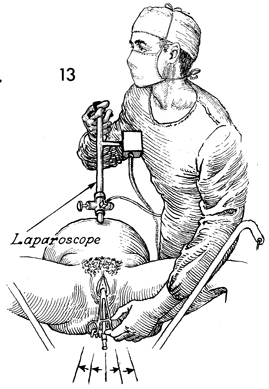

Laparoscopy Technique

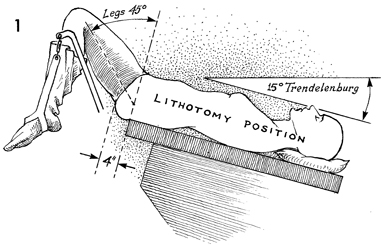

The basic procedures for laparoscopy are the same whether

this form of surgery is used for diagnosis or surgical treatment. Either

a single- or a multi-incision technique may be employed. For the former,

the operative laparoscope is used. For the latter, the laparoscope

without operative channels is passed through the first incision, and

one or more operative instruments are inserted through the other incision

as required. The operative scope is attached to a video monitor to

enlarge the operative field and allow the operating room team to observe

the procedure. In simple diagnostic or surgical procedures, the operative

laparoscope has an advantage over the diagnostic laparoscope in that

it allows an operative instrument to be passed down its channel either

to stabilize structures or to aspirate blood or fluid from the operative

field.

The operation is a simple, safe, cost-efficient way

of diagnosing and treating problems within the female pelvis.

Physiologic Changes. Physiologic

changes occur when laparoscopy is used to lyse adhesions, fulgurate

endometrial implants, biopsy ovaries, remove ectopic pregnancies,

and relieve obstruction in the Fallopian tube or obstruct the tube

for sterilization by electrocauterization and/or the application

of a Silastic ring or clip.

Points of Caution. Care must be taken to ensure that

the needle for pneumoperitoneum is within the peritoneal cavity. The

trocar should always be kept sharp, or a disposable tocar should be

used. Electrocauterization should proceed with extreme caution.

Technique

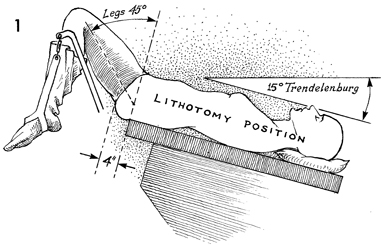

The surgeon who is knowledgeable

about all aspects of laparoscopy should position the patient

in the lithotomy position modified to conform to the special

requirements of the procedure. The legs are not placed in the

standard 90° flexion, as in

the classic dorsal lithotomy position, but are positioned at

45°flexion

from the hip. It is extremely important to have the buttocks

at least 4 inches off the end of the operating table to facilitate

manipulation of the cervical and intrauterine instruments into

an advantageous position for maximum visualization of the internal

genitalia. The operating table should be slanted to a 15° Trendelenburg

position to displace the intestines out of the pelvis and into

the upper abdomen. It is more comfortable for the operating surgeon

to have the patient's arms down at her sides than extended on

an arm board. We frequently insert the needle for intravenous

infusion into the forearm, then place the arm at the patient's

side and secure it with a draw sheet that has been previously

placed underneath the patient. |

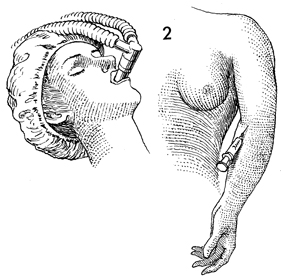

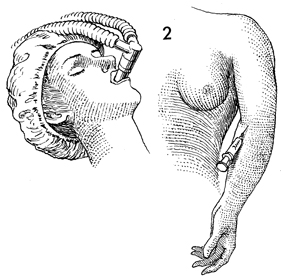

Anesthesia for laparoscopy can be either

general or local. If general anesthesia is used, it should be

administered by the same standard techniques as used for major

abdominal operations. One should not attempt to achieve surgical

planes of anesthesia with tranquilizers or narcotics.

If local anesthesia is used,

it should be accompanied by intravenous sedation prior to the

operative procedure. We prefer to sedate the patient with 50

mg meperidine (Demerol) and 10 mg diazepam (Valium) after she

is placed on the operating table. In general, we limit our use

of local anesthesia to laparoscopy sterilization procedures and

other short diagnostic procedures that do not require extensive

intraperitoneal manipulation of the tubes or ovaries. |

A bimanual pelvic examination should precede

all laparoscopy procedures. |

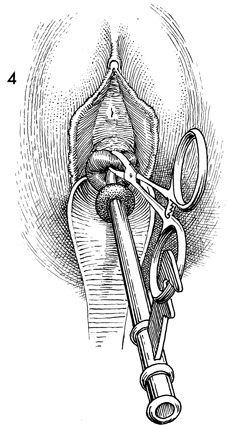

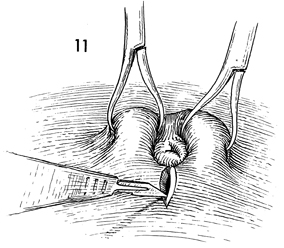

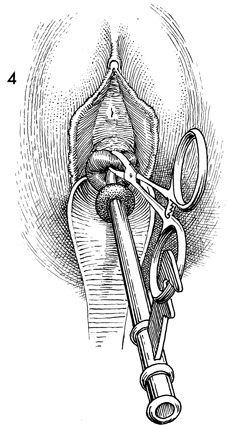

The procedure is started by

grasping the anterior lip of the cervix with a wide-mouthed Jacobs

tenaculum attached to a Rubin intrauterine cannula. Exposure

of the cervix should be obtained with a narrow curved Sims posterior

retractor rather than a wide, flat, posterior vaginal retractor.

The large retractors produce pain, sometimes initiating a cycle

of pain and anxiety that may make local anesthesia ineffective. |

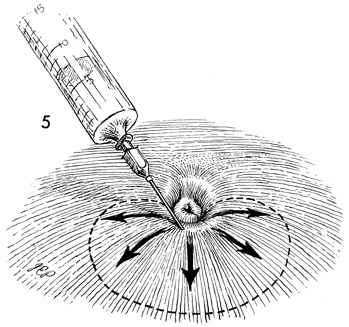

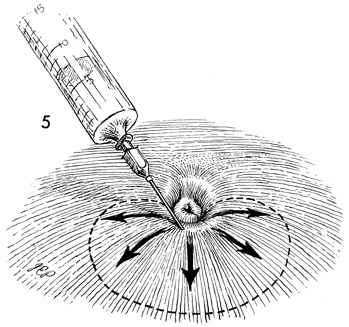

If local anesthesia is used,

the inferior rim of the umbilicus is thoroughly infiltrated with

1% Xylocaine solution in a semicircular manner from the 9 o'clock

position around to the 3 o'clock position on the umbilicus. The

first injection of Xylocaine should be given at the 6 o'clock

position on the inferior rim of the umbilicus, and the needle

should be advanced underneath the skin as shown. In addition,

approximately 2 mL should be infiltrated into the rectus fascia

and muscles. |

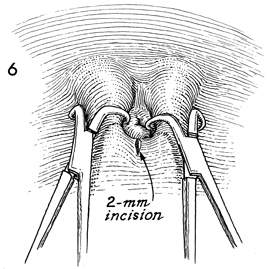

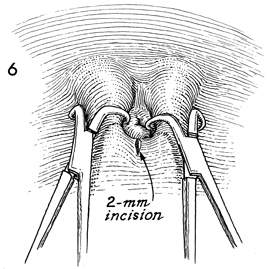

Adequate

countertraction on the anterior abdominal wall is necessary.

Although some rely on a large pneuoperitoneum to provide adequate

countertraction, we elevate the lower midline of the abdomen

for this purpose. We have found that placement of the two towel

clips, one each at the 5 and 7 o'clock positions on the inferior

rim of the umbilicus, offers the best method of countertraction

for insertion of the pneumoperitoneum needle and the trocar.

After the towel clips have been placed, a 2-mm incision is made

in the inferior rim of the umbilicus. |

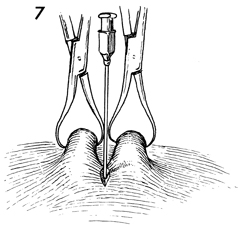

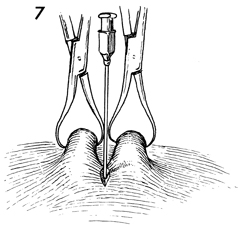

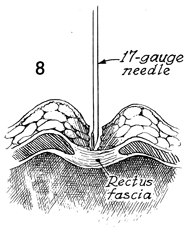

The towel clips are elevated slightly and

a 17-gauge Tuohy epidural needle is advanced through the 2-mm

incision down the fascia. |

No attempt is made to penetrate the fascia

with the initial insertion of the Tuohy needle. |

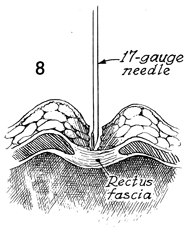

The needle is tapped against

the fascia several times at a 90° angle to the plane of

the body. The towel clips are further elevated for countertraction,

and the needle is pushed through the rectus fascia with a short

quick motion that advances the needle through the peritoneum.

This technique reduces the possibility that the needle will slide

off the rectus fascia and into the subcutaneous space. |

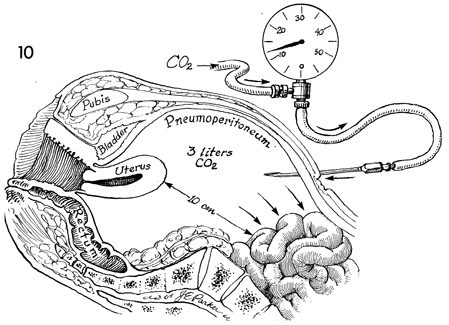

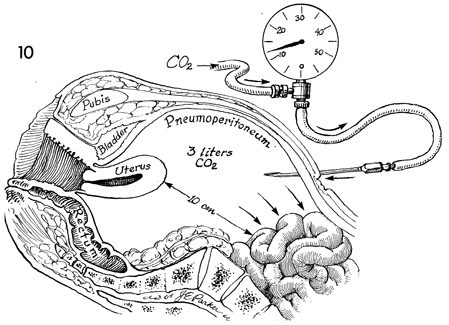

The pneumoperitoneum needle

is immediately attached to the gas line from the carbon dioxide

machine. The gas is allowed to flow and the pressure is observed

to ensure that it is approximately 15 mm Hg. We have found the

gas pressure method to be the most accurate way to determine

proper placement of the pneumoperitoneum needle. Other techniques

are the water-drop test and the saline-syringe test. With the

gas pressure method, using a large-bore 17-gauge needle, a pressure

greater than 15 mm Hg is an indication that the pneumoperitoneum

needle is not in the free peritoneal space but is either up against

a piece of bowel, in the omentum, or in the supraperitoneal space.

It should be further adjusted by advancing it, twisting the bore

180° or withdrawing it slightly until such time as the

pressure manometer indicates a pressure of less than 15 mm Hg.

There are times when the gas line or the needle itself has an

intrinsic obstruction that results in elevated false gas pressure

readings. In these cases, one would accept a gas pressure of

10 mm Hg above the baseline pressure. Generally, for sterilization

procedures such as the Silastic band operation, no more than

2 liters of carbon dioxide are needed. In electrocoagulation

of the Fallopian tubes or other surgical procedures, however,

a higher volume of gas is needed in order to obtain a larger

displacement of bowel away from the pelvic organs to reduce the

possibility of gastrointestinal burns. For diagnostic procedures,

it is better to use at least 4-5 liters of gas for maximum displacement

of bowel. Therefore, it is better to perform diagnostic and more

extensive surgical procedures under general anesthesia, as few

patients can tolerate 5 liters of gas in the peritoneal cavity

under local anesthesia. |

The 2-mm incision is extended to 1 cm. |

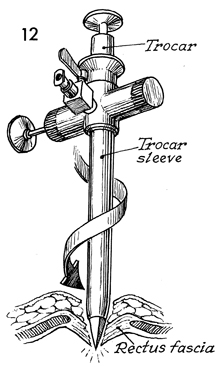

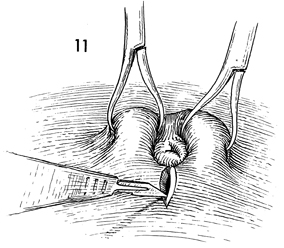

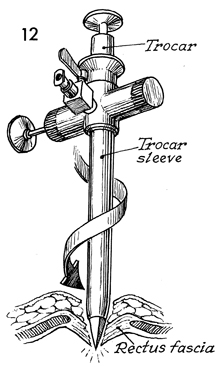

The laparoscope trocar and sleeve are inserted

through the umbilicus incision in a twisting corkscrew technique

that involves pushing the trocar down to the rectus fascia; with

a short twisting corkscrew motion, the trocar is pushed through

the rectus fascia while pulling up on the towel clips for countertraction.

By using the short thrust and corkscrew motions, the surgeon

advances the instrument progressively through the rectus fascia,

avoiding a sudden thrust that might slip and contact the intra-abdominal

or retroperitoneal organs. |

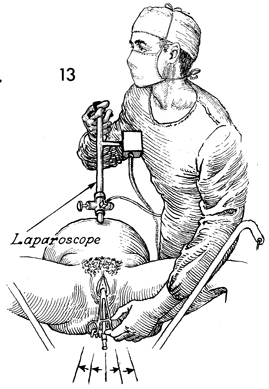

The trocar is removed from the

sleeve, the gas hose is connected to the gas port on the trocar,

and the laparoscope is advanced down the trocar sleeve into the

pelvis. The angle of the insertion of the laparoscope through

the sleeve and through the abdominal wall should be approximately

15-20° to the plane of the patient and not at 90° angle, to avoid touching the lens against the surface of the

bowel and the omentum. Such contact produces a pink or yellow

blur instead of the recognizable abdominal structures. By holding

the laparoscope in the right hand and moving the left hand between

the patient's legs and grasping the Jacobs tenaculum and Rubin

cannula, the uterus can be manipulated to either side or in the

anterior-posterior plane for maximum visualization of all the

internal genitalia. |

By depressing the Rubin cannula

and Jacobs tenaculum, the surgeon can move the uterus into an

anteflex position, thereby making the cul-de-sac, broad ligament,

tubes, and ovaries visible. When maximum visualization of the

structures is achieved, a nurse or assistant holds the Rubin

cannula and Jacobs tenaculum in the desired position while the

laparoscopist moves his left hand

up to support the operating laparoscope and his right hand to

perform the surgery (obviously, the reverse is true for those

surgeons who are left-handed).

|

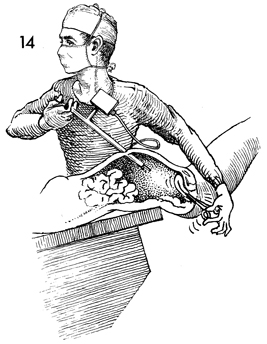

Multi-incision

Technique

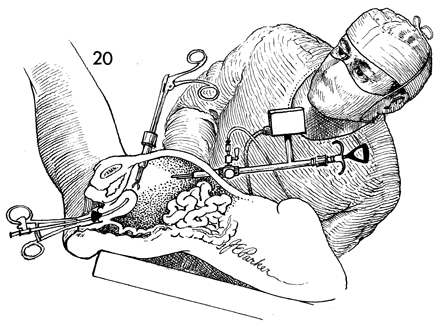

Multi-incision laparoscopy

is useful in most advanced surgical techniques. These cases

include egg retrieval for in vitro fertilization, ovarian biopsy,

extensive lysis of adhesions, extensive fulguration of endometriosis,

the occasional removal of an intraperitoneal foreign body,

laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, and resection of

ectopic pregnancy. |

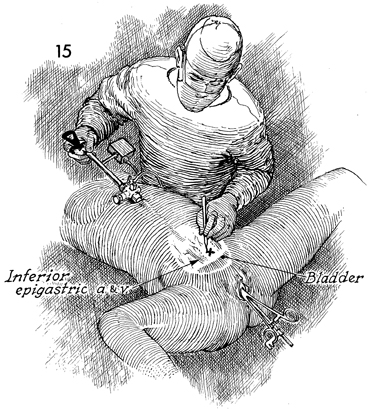

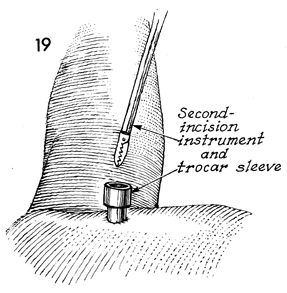

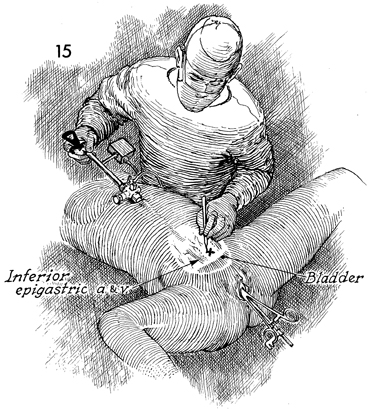

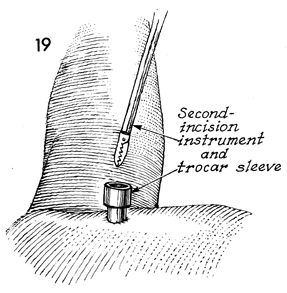

The first step in the insertion of a second

instrument is to transilluminate the lower abdominal wall and

select an avascular site for the incision of the second-incision

trocar. We prefer the left and right lower quadrants where it

is more advantageous to have the second-incision instrument at

a right angle to the first-incision observation instrument. In

all cases, however, an avascular area of the lower abdomen should

be selected with special care to avoid the inferior epigastric

artery and vein lateral to the rectus muscle. |

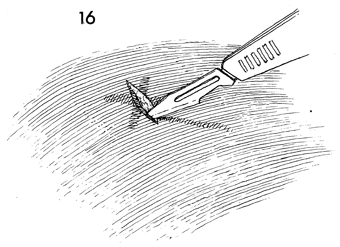

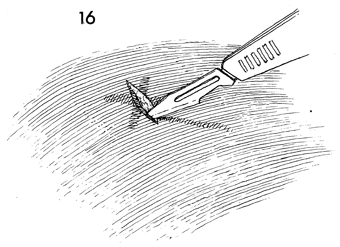

A 6-mm incision is made over the avascular

area down to the fascia, and the fascia is lightly incised with

the scalpel. |

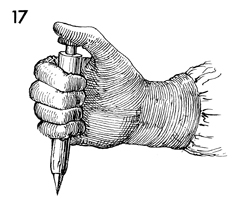

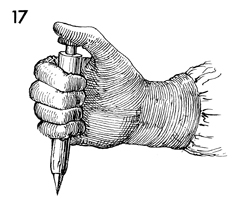

The second-incision trocar and sleeve are

held in a dagger fashion with the thumb on top of the trocar

and the fingers wrapped around the trocar sleeve. |

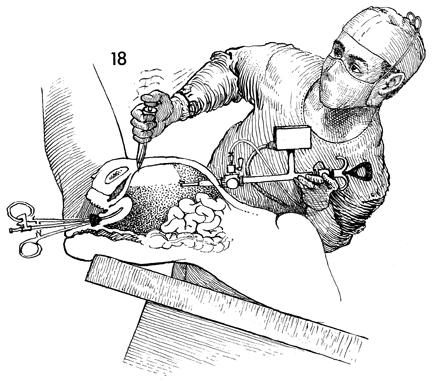

The second-incision trocar and

sleeve are inserted through the second-incision down to the fascia.

At this point, the surgeon looks through the laparoscope or the

attached video screen and slowly advances the second-incision

instrument until it has perforated the peritoneum. Occasionally,

it may be helpful to use the first-incision instrument as a source

of countertraction by using it to elevate the anterior abdominal

wall against the area where the second-incision trocar and sleeve

are penetrating the peritoneum. |

The second-incision trocar is withdrawn from

the second-incision sleeve and is now ready to receive operative

instruments. |

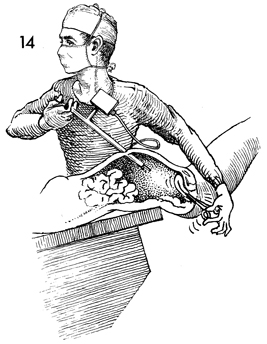

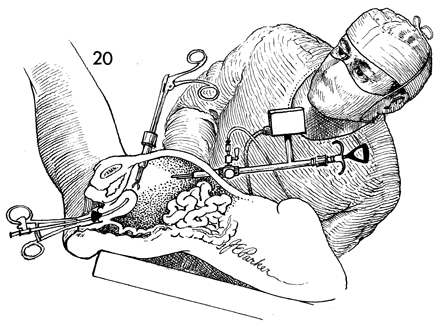

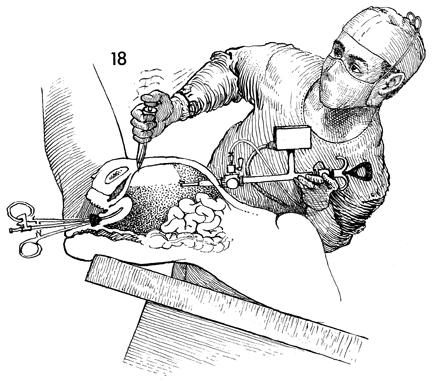

The Rubin cannula and Jacobs

tenaculum are held by a nurse or assistant in the most advantageous

position. The surgeon holds the laparoscope with his left hand

and the second-incision instrument with his right hand. Note,

that as shown, an operating laparoscope is used for the first

incision. This allows a second instrument to be inserted into

the abdominal cavity to facilitate the desired surgery without

a second incision. The ovary or Fallopian tube can be stabilized

for biopsy or lysing peritubal adhesions. |

|