Abdominal

Wall

Pfannenstiel Incision

Maylard Incision

Panniculectomy

Incisional Hernia

Repair

Abdominal

Wound

Dehiscence and

Evisceration

Massive

Closure

of the Abdominal

Wall With a One-Knot

Loop Suture

Hemorrhage

Control Following Laceration

of Inferior Upper

Epigastric Vessels |

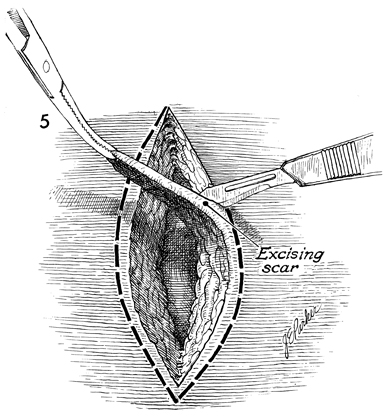

Incisional Hernia Repair

Although improved suture materials (stainless steel wire, monofilament

nylon, Prolene, etc.), in addition to improved techniques in closing

the rectus fascia, have significantly reduced the incidence of incisional

hernia, such hernias do occasionally occur.

They are, interestingly, rarely seen with the lower transverse Pfannenstiel-type

incision. The etiology of incisional hernia can range from wound infection

and subfascial hematoma to a disruption of the suture line secondary

to coughing during the immediate postoperative period.

The purpose of the operation is to close the hernia and reinforce the

fascia to reduce recurrence.

Physiologic Changes. The overall comfort of a patient

is increased by eliminating the incisional hernia. Although the incidence

of bowel obstruction is small, it can occur. The traditional physiologic

principles of hernia repair apply equally to incisional hernias and

inguinal hernias (i.e., high ligation and excision of the hernial sac

and double reinforcement of the rectus fascia).

Points of Caution. Care must be exercised in making

the initial incision to avoid lacerating a loop of bowel adherent in

the hernial sac.

Adequate mobilization of both fascia and subcutaneous tissue should

be made to allow tissues to come together without tension.

Technique

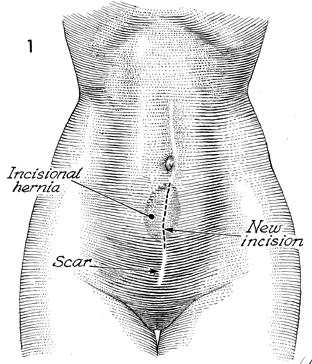

The patient is placed on the operating table

in a supine position. Palpation of the abdomen reveals the hernia.

No attempt is made to excise the cutaneous portion of the hernial

sac. A midline incision is made over the hernial area, excising

the previous scar. |

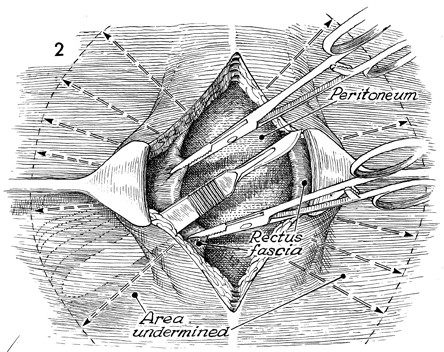

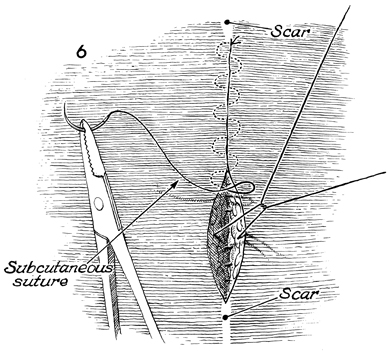

The incision is carried down to the hernial

sac, which generally represents the peritoneum or attenuated

rectus fascia. The hernial sac is located, a small hole is made,

the sac is completely explored with the finger, the peritoneal

incision is extended, and all contents are removed from the sac.

The margins of the sac itself are identified and excised with

scissors. The margins of the rectus fascia are then identified,

and the skin and subcutaneous fat overlying the rectus fascia

are sufficiently mobilized to allow the rectus fascia to be developed

as two overlying flaps similar to a double-breasted coat. This

is initiated by placing a retractor under the skin margin, applying

two Kocher clamps to the margin of the rectus fascia, and dissecting

the skin and subcutaneous tissue from the rectus fascia with

sharp dissection. The same procedure is carried out on the opposite

side. The peritoneum is closed with a running 0 synthetic absorbable

suture. |

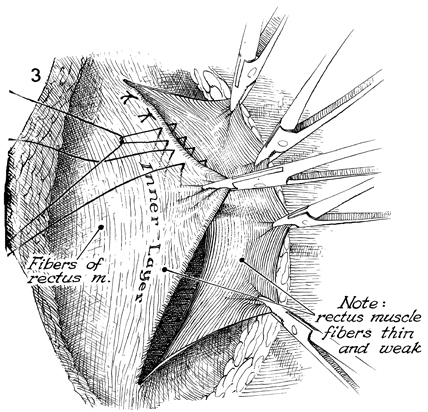

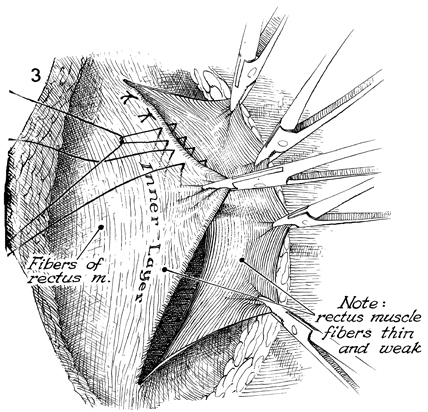

A row of 28-gauge stainless steel wire or

0 nylon sutures is placed in the base of one flap and through

the margin of the opposite flap as interrupted mattress sutures.

These are tied in progression. The margin of the overlying flap

is elevated by traction with small hemostats. |

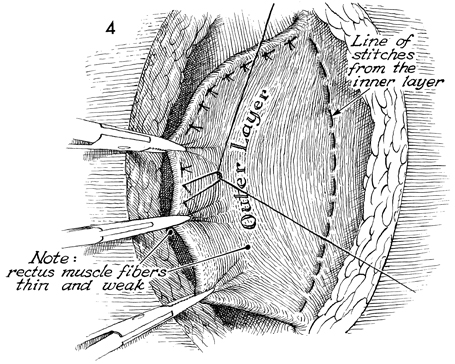

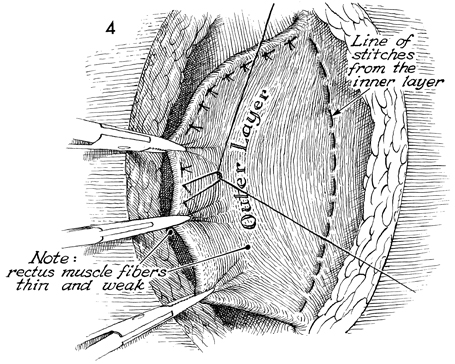

The line of sutures from the

inner flap is completed. The outer layer of rectus fascia is

pulled over the inner layer and sutured with interrupted 28-gauge

wire or 0 nylon mattress sutures. |

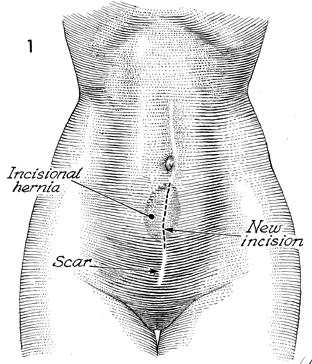

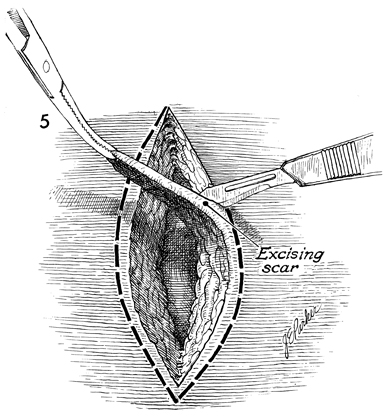

Any existing scar tissue in the skin and

subcutaneous incision is surgically excised. |

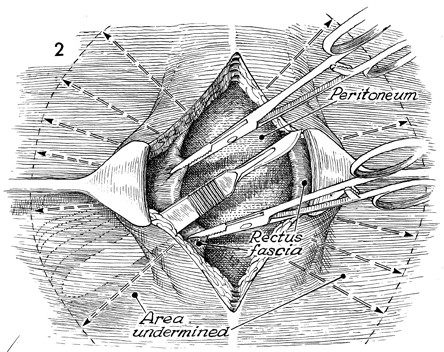

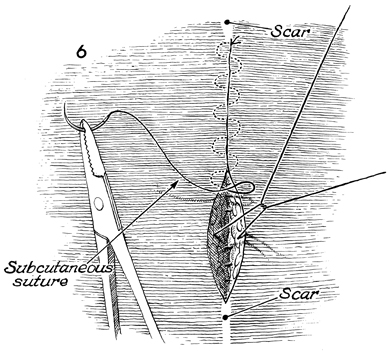

The subcutaneous tissue is

closed with interrupted 2-0 synthetic absorbable suture, and

the skin is closed with a subcutaneous 3-0 Dexon suture. |

|