|

||||||||||

Abdominal

Wound Massive

Closure Hemorrhage

Control Following Laceration |

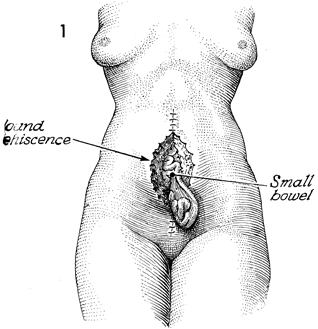

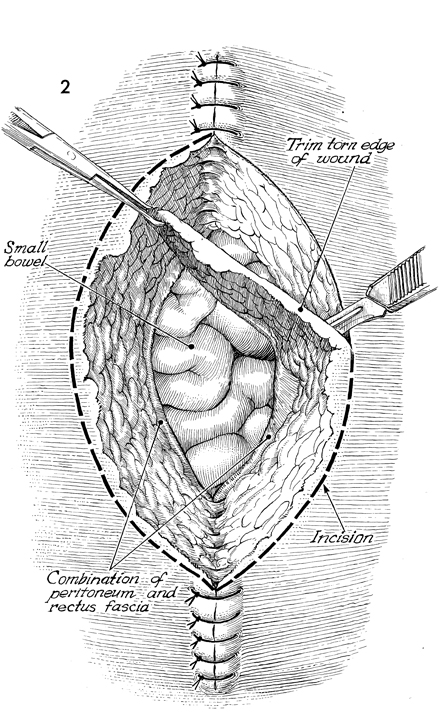

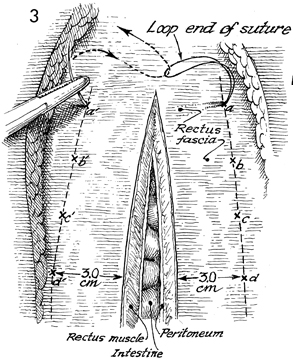

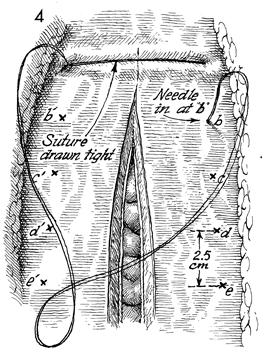

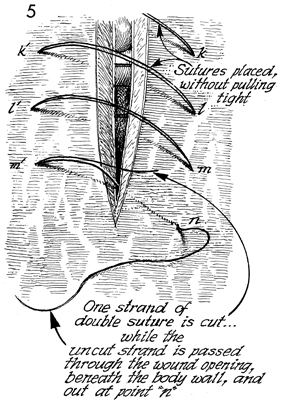

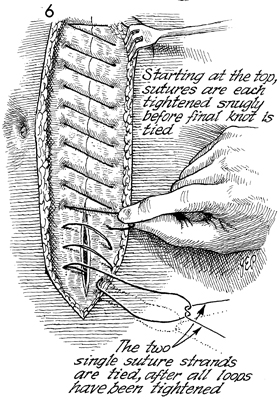

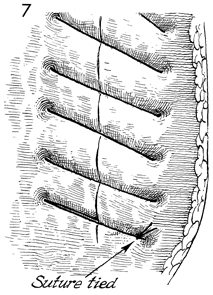

Abdominal Wound Dehiscence The seepage of serosanguineous fluid through a closed abdominal wound is an early sign of abdominal wound dehiscence with possible evisceration. When this occurs, the surgeon should remove one or two sutures in the skin and explore the wound manually, using a sterile glove. If there is separation of the rectus fascia, the patient should be taken to the operating room for primary closure. Wound dehiscence may or may not be associated with intestinal evisceration. When the latter complication is present, the mortality rate is dramatically increased and may reach 30%. The basic principles of management of abdominal wall dehiscence and evisceration are early diagnosis and surgical closure. The latter is accompanied by mass closure with wide sutures of heavy delayed synthetic absorbable suture. The purpose of the operation is to close the abdominal wall. Physiologic Changes. Dehiscence may stem from wound hematomas or from excessive intra-abdominal pressure secondary to abdominal coughing or vomiting that has disrupted the sutures. It is most commonly seen in patients with properties of poor wound healing, such as patients with diabetes, oncology patients, and patients taking steroid medications. Points of Caution. All attempts should be made to diagnose and manage this problem promptly to minimize the risk of intestinal evisceration. All sutures should be placed prior to tying any one suture. Technique

|

|||||||||

Copyright - all rights reserved / Clifford R. Wheeless,

Jr., M.D. and Marcella L. Roenneburg, M.D.

All contents of this web site are copywrite protected.